Stony Brook 200 System Overview

In the spring of 2025, Sarah Belle Reid and I traveled to Long Island, New York to visit Stony Brook University: home of one of the earliest Buchla Series 200 systems. Together, we scripted and produced a video about the instrument, detailing its features, general historical context, and some particularly interesting aspects of its overall design philosophy. After several months of editing, we're happy to present the result, which is now available on Sarah Belle Reid's YouTube channel. We hope that you'll enjoy it.

The Stony Brook 200 System: Context

Composer Bülent Arel commissioned the creation of this system c. 1971, in order to act as the centerpiece of the new electronic music studio at Stony Brook. Arel had previously established the Yale electronic music studio, and had worked extensively at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. In each of these studios, Arel worked with the then-new Buchla 100, producing some wildly dynamic, gestural, and virtuosically-executed pieces of tape music. Once the Stony Brook studio was in place, he was soon joined by his colleague and former pupil Daria Semegen—who still oversees the studio to this very day. Semegen is a brilliant composer and a kind, humorous, and inspiring soul. We cannot thank her enough for welcoming us to Stony Brook.

Arel and Semegen each employed this 200 Series system in the production of new works, including compositions such as Arel's Mimiana and Fantasy and Dance for Viols and Tape, as well as Semegen's Arc and Spectra. These seldom-discussed works are deeply dynamic and idiosyncratic—blending the Buchla's capacity for gestural and automated behavior with Arel and Semegen's mastery of tape music composition and editing techniques. The pieces offer a unique blend of the then-new techniques of voltage control and time-tested methods of tape-based music-making, and nothing else that I've heard sounds quite like them.

Historically speaking, aside from its role in some truly excellent music, the Stony Brook 200 system is a unique artifact. It is one of the largest early 200 systems ever produced, containing at least one (and as many as five) of each module that was available at the point of the 200's introduction. This includes some particularly rare and elusive modules, such as the Model 226 Quadraphonic Monitor / Interface and the Model 264 Quad Sample & Hold / Polyphonic Adaptor. And, while many systems from this era have changed hands or been altered/dismantled over the decades, this system is still in its original form, in its original home. It has been very well-cared-for over the course of its 50+ years of existence, and aside from some minor issues, is still in excellent functional condition to this day.

The Electric Music Box Series 200 system at Stony Brook University, Spring 2025.

Needless to say, this is a rare and exceptionally well-preserved instrument, and we were honored to spend time getting to know it. Given that opportunities like this are so rare, we're pleased to offer the video above, which should hopefully demonstrate why instruments like this are so special. There's much to be said about the 200 and its historical significance, but for now, I'll let the video speak for itself—and we'll share some additional thoughts from Reid below.

-RG

Perspectives from Sarah Belle Reid

Over the years I’ve had the privilege of working with many different Buchla instruments, ranging from the very first 100 series modular system to some of the computer-based instruments from the late ’70s and ’80s. Most of my prior experience with 200 series systems, however, had been focused on later iterations of the 200 series design from the late 1970s—systems that included modules such as the Model 259 Programmable Complex Waveform Generator, Model 296 Programmable Spectral Processor, and the Model 266 Source of Uncertainty, among other iconic and idiosyncratic modules.

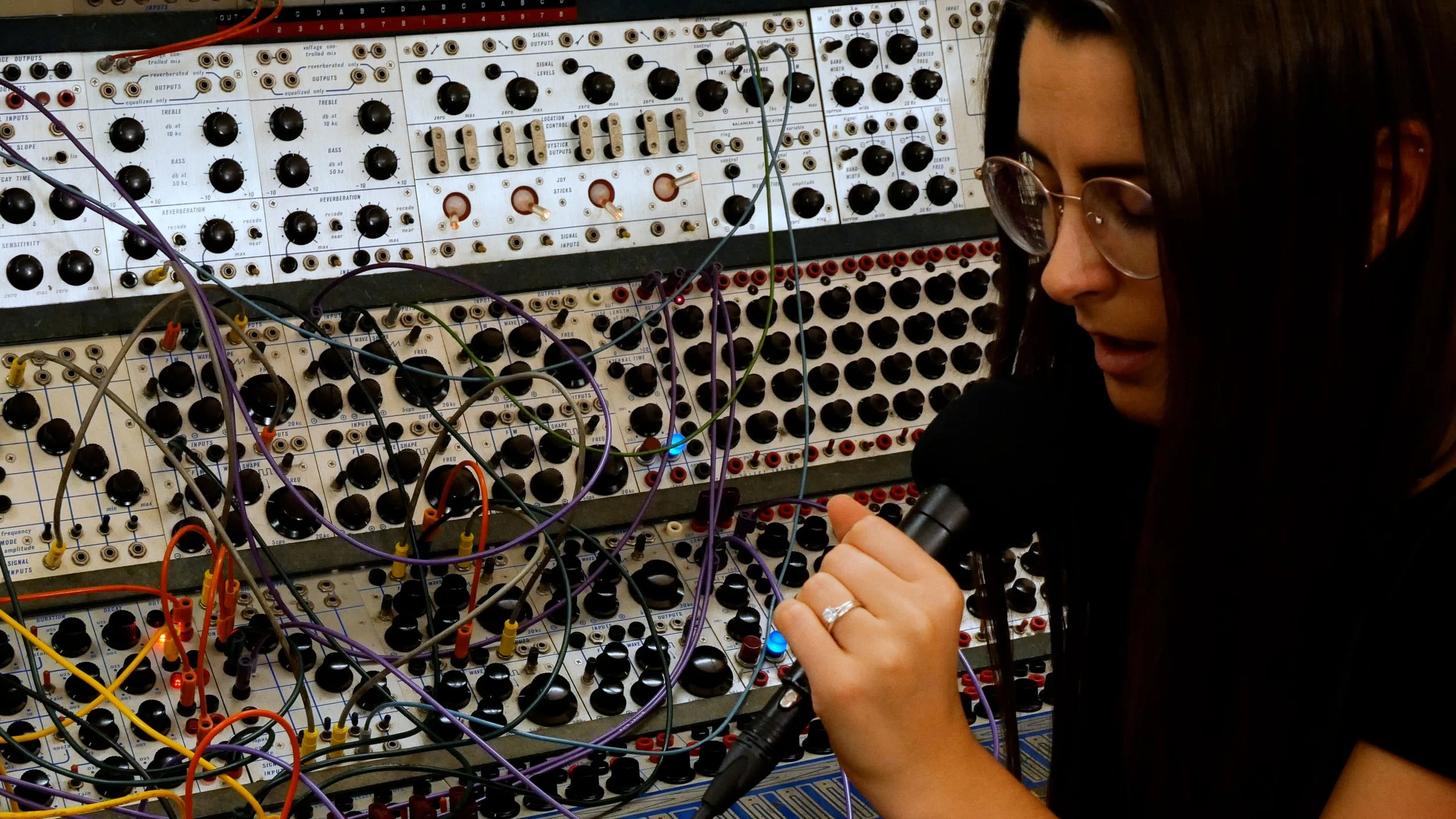

Sarah Belle Reid with the Stony Brook Buchla 200 system, Spring 2025.

Modules like these are fairly well-known, and considered by many to be integral to the 200 series “experience.” However, the 200 series had been in production for years before these modules existed: early 200 systems look quite different than popular perception might suggest.

My time working with the early 200 series system at Stony Brook really helped me to fill in some of the gaps in my knowledge and experience, and to more clearly understand the progression that Buchla’s designs took, from the earliest 100 series modules, through to the later 200 modules I was already familiar with.

What I find endlessly fascinating about studying these instruments is not only learning the technical details of each design, but also reflecting on the progression of ideas and philosophies that informed their development. When you look closely across the iterations of Buchla’s instruments, you see how deliberate and considered every design choice was. Each new module introduces workflow refinements, new possibilities for interaction, and broader horizons for what becomes possible in music-making.

In this way, I’ve come to think of Buchla’s instruments less as fixed endpoints and more as living milestones throughout his life’s work. Each version of the instrument wasn’t just “finished,” but was instead a kind of stepping stone across his trajectory as an artist and instrument designer. People would play with it, stretch it, and explore its possibilities, and through that process, Buchla would listen, brainstorm, and discover the next important step to take in his designs.

The Model 226 Quadraphonic Monitor / Interface

One of the most striking differences I felt when moving from the 100 to the 200 was in the sense of reciprocity between performer and instrument. With the 100, I often found myself physically shaping every single sound—my hands on attack times, pulse speeds, and waveforms—like I was really playing the instrument note by note. With the 200, however, the relationship felt more bi-directional. Its expanded CV processing and numerous points of interaction made it easy to create situations where it really felt like the instrument was listening, responding, and even surprising me. Rather than me alone pulling sound out of the system, it began to feel like the system was also pushing me into new directions I wouldn’t have thought to explore on my own.

That kind of dynamic relationship is something I love, and something I actively strive to cultivate with all of the instruments I work with. I feel incredibly grateful for the opportunity I had to spend time with this Buchla 200 system, to get to know it on such an intimate level, and to share some of those insights with others.

The Model 217 Multiple Touch Controlled Voltage Source

In addition to the music and patch demos that made it into my “Electric Music Box” video, I also recorded some additional music on the 200 system (including one particularly interactive patch centered around the envelope follower and a microphone input) that I plan to share in the near future.

Looking somewhat farther ahead, the Buchla Archives and I have a number of other research- and history-focused projects in the works. One upcoming video will be a deep dive into the Touché (c. 1980), a rare polyphonic keyboard instrument designed by Don Buchla with software by David Rosenboom. I’m excited to keep exploring and sharing more of these instruments’ stories, so stay tuned for much more to come!

-SBR